Shuchi Kothari is a filmmaker and academic, based at the University of Auckland, where she where she convenes the Screen Production programme. She’s written three short films: Fleeting Beauty; Coffee and Allah;and Clean Linen; and two features: Firaaq with Nandita Das, who also directed; and Apron Strings, with Dianne Taylor, directed by Sima Urale. Shuchi was co-creator of A Thousand Apologies, New Zealand’s first prime-time Asian series; and was the writer and presenter of The Taste of Place: Stories of Food and Longing.

Shuchi is also a producer of most of these projects; and one of the founders of the Pan-Asian Screen Collective. I interviewed her late in 2018, after the first short she’s written and directed, Shit One Carries, opened at the New Zealand International Film Festival (NZIFF).

Marian How did you feel about Shit One Carries opening at the New Zealand International Film Festival?

Shuchi It was lovely because everything I’ve written and produced in this country and in India has been accepted by the festival, which has been fabulous, but if they hadn’t accepted this one I would have said, ‘Okay they like me as a writer, they like me as a producer, but they don’t think I can cut it as a director’. As I’d said to writer-director Jackie van Beek — who had looked at my pre-final cut and recommended a really interesting change in the edit — I don’t feel a huge amount of pressure with this film because it was an experiment to see how my writer/producer instincts manifest as a director. I don’t consider myself a director nor am I interested in changing the future direction of my filmmaking life. Plus look at the appalling statistics about women directors around the world, so everyone’s got to do their bit.

When I began film school in the U.S. in 1990, within the first week I shifted out of the directing major into a writing major. This particular tutor was so full of testosterone. He’d shout at everyone in the studio, saying, ‘you’ve gotta be an asshole to be the director’ ‘you’ve gotta be the goddamned boss’ — just the usual attitude of that time. And I thought to myself ‘I’m not any of these things and I don’t want to be these things’. I left class at the end of that session, went straight to the graduate adviser and asked if I could shift to screenwriting. He happened to be the head of the screenwriting area. He just smiled and said ‘I’m so glad because when I read your application I was hoping that you would come to my side of the department’.

And I never regretted it. I’ve always loved screenwriting. I produce projects more by circumstance rather than choice. Writing’s where it’s at for me.

My choice to direct Shit One Carries didn’t stem from any unhappiness about the way my writing has been treated by other directors. On the contrary, all the six women directors with whom I’ve worked have interpreted my writing in very interesting ways. As I said earlier, I just wanted to give myself a challenge — how would I do something that I’ve done on the page (in the way that writers do direct on the page) for real on set? It’s more a kind of provocation to myself rather than proving anything and that though terrifying, was liberating.

M And what did you learn?

Shuchi As a producer I have been on set a lot. So the machinations of the set weren’t a revelation. What was interesting is that space in performance where the script leaves you. And this was my first time negotiating that space, being very much in that moment. Not at all beholden to what was on the page but only to the emotion that the scene needs to convey. Prior to Shit One Carries I’d co-directed a docu-fiction film with Sarina Pearson a couple of years ago, so that was as far as my experience with actors went. Working with actors was my big challenge. And it was great because it meant I rehearsed a lot.

I did make my job a bit harder because Shit One Carries is set in Gujarat, India. I wasn’t prepared for some of the realities of shooting in Ahmedabad. Firstly, casting was not as simple as I thought. Since realism is not the chief aesthetic of most Indian film and television, finding actors who were fluent in the Gujarati language yet not immersed in that heightened or theatrical mode of performance was not easy. So I decided to cast as many non-actors as I could. This meant we had to rehearse a fair bit and with each rehearsal I found myself enjoying the process and loving the casual rawness they brought with them.

M What realities were you unprepared for?

Shuchi Let me talk about all the good stuff first. I owe a lot of this film’s success to my Director of Photography, Mrinal Desai.

I’d worked with him on a documentary earlier and I was determined that if I ever shot anything in India again, I’d go to him first. Besides, it was something he said while caring for his aged father that led me to make Shit One Carries. He guided me through my inexperience in a rigorous and gentle manner.

Because I wanted to shoot the film without any close ups, in wide shots from an observational point of view, I knew it was a risky decision. He shot the whole rehearsal for me two months before the actual shoot, so I could cut a few scenes to see if the emotion held up from a distance. He also brought with him from Bombay a brilliant gaffer and a soundie whom I loved so much that I worked with her again at the first opportunity.

So that was all good. But my co-producer and I really struggled to get a good production team in Ahmedabad. It is not a hub of filmmaking though lately it’s doing a lot of Gujarati language cinema. For instance films in Ahmedabad don’t shoot sync sound. So we had to get all our sound team from Bombay. Despite regular production in the state, the industry is not professionalized. So things like making call sheets or reading call sheets regularly or just basic health and safety protocols were new for the local team.

Everyone was enthusiastic, and some non-film friends rescued me, but in terms of that creative and dynamic relationship between the director and Heads of Department of art, costume, make-up, I’d have been better served if I’d shot the film in Bombay, or of course in New Zealand. But I had to shoot it in Ahmedabad. I always imagined a particular type of house in which the whole story unfolds. And that house was in Ahmedabad.

M Why did you set it there?

Shuchi The idea of writing about awkward intimacies between adult children and their ageing parents came about at a particular moment. I think my friends and I have hit that age where our parents are dying or passed away or ill. We’ve become their caregivers and negotiating that space of physical intimacy can be difficult. It doesn’t come easily to everybody. Then when you live in one country and your parents in another, it complicates things even further.

When I was shooting a documentary on Indian textiles and fashion in India, my mother had a fall and was bedbound. Nurses and attendants would come and go but up until that moment I had not experienced my mother’s physical dependence on others. During this period Mrinal Desai was having similar struggles with his bedridden father but on a much more serious level. One time I asked how his day was and he replied, ‘I spent the morning trying to figure out who’s going to wipe my father’s arse’. And this line just stayed with me.

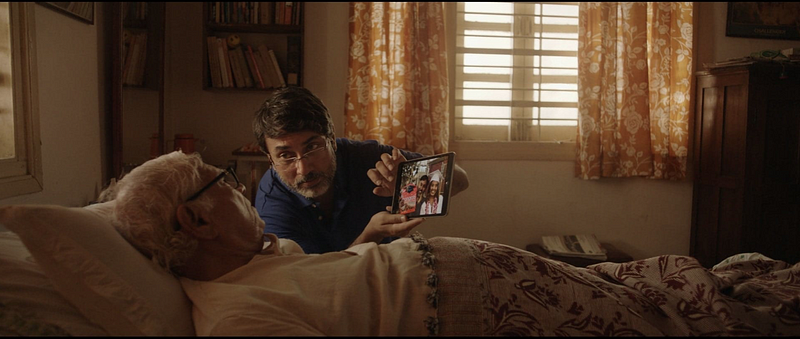

As soon as I boarded the flight for the long journey from Ahmedabad to Auckland, I began typing that one sentence which then led to this story of a son returning from California to look after his father with whom he has a prickly relationship. This makes caregiving even harder.

The film unfolded in my mind in Gujarati, and was set in Gujarat. I wanted to commit to that. Language is such an integral part of how you understand a character or how a character understands themselves. Shit One Carries has English, Gujarati and Hindi because that is often the linguistic reality of urban Gujarat.

When I was writing Nandita Das’ directorial debut film Firaaq, characters spoke four languages and often code switched. I’m currently writing another feature set in Ahmedabad that is also multilingual. So I’ve always been concerned about how we express ourselves as multilingual people, as transnationals working and living across places, between places sometimes and occasionally, lost in translation. Places and cultures are idiomatic and therefore some stories more naturally belong to them.

I did ask myself for a moment if somehow I could transplant this father-son story to New Zealand and then apply for funding to the New Zealand Film Commission (NZFC). But it just didn’t translate. The whole layer of caste and hierarchies within caregiving roles that are integral to the film don’t play out the same way in New Zealand. Sure, the awkwardness between father and son is not particularly an Indian or a non-Indian thing. But I did feel that those roles of care such as who washes your body, who cleans your bottom, who gives you an injection, who can cook, and who can give you a cup of tea are often defined around caste-lines in India. So that important layer of the story would have been lost had I transplanted it to Auckland.

M So you had to bypass the usual routes to funding.

Shuchi The NZFC’s short film fund is for ‘New Zealand stories’. There are also stipulations around where the money is spent. Even if I did all my post-production in New Zealand (which I did, by the way), the production spend was all in India. The actors were all Indian, the whole crew was Indian except for two New Zealanders who travelled from Auckland: Peter Simpson, a long time collaborator, and Pani, an ex-student who wanted to experience a set in India. Sure, I’m a New Zealander telling this story but there is nothing about the characters that’s New Zealand so I simply wouldn’t have qualified for NZFC funds.

This is when I decided to apply to the University of Auckland’s Faculty of Arts Research Development Fund. This is a competitive fund that I, as an academic, can access. Also, because I was directing fiction for the first time, it was also part of my professional development as a filmmaker.

I took nothing for granted. The research committee said they really appreciated the care I’d taken in putting the application together and also in budgeting because I was very verycareful to make sure that everything went on to screen but also creatively making things work without having to spend too much switching locations and things like that; just making the containment of the film work to its advantage. I always tell my students this too — when you apply for funds to make films don’t take anything for granted. Filmmaking is a privilege not a birthright.

I was dead pleased to hear that my application had been successful but I still had to raise another twelve thousand dollars on my own. But thank god for UoA funding because for people like me whose stories may be set here, or just as likely overseas, justifying ‘New Zealandness’ is really painful. I strongly believe that if public funding mandates ‘New Zealand stories by New Zealanders’ we need to deepen our understanding of New Zealanders and widen our definition of New Zealand stories. If you come from other places and become a Kiwi your ‘other places’ have an imprint on you, on your being a New Zealander. I’m a Kiwi-Indian. I am this hyphenated person. Both places carry the other place.

I find it very restrictive to think of New Zealand stories as the ones that are only set here. For instance Coffee & Allah was not about Indians. It was about an Ethiopian Muslim woman’s desire to communicate. Fleeting Beauty was about a ‘colonial subject’ rewriting Indian history by painting with spices of her Pakeha lover’s body. In Apron Strings Dianne Taylor and I used food as a metaphor to speak about difference and ‘othering’.

I think my own difference/otherness is always in dialogue with the work I make. I’m interested in this struggle to belong or not belong; the choices that one makes or is allowed to make; the cost of adaptation, the loss of empowerment, structural racism, our relationship with tangata whenua and so on. And also to acknowledge our varying privilege so we don’t conflate immigrants, migrants, exiles, refugees in one basket of diversity or minority. I always tell my students to render people’s experiences in a nuanced fashion. You know, Zahara the lead actress in Coffee & Allah came here as a refugee, from Ethiopia to Kenya to Auckland. I cannot pretend for a moment that my experience of displacement is the same as hers.

Having said that, despite the difference in our experiences, there are times when bunch of us hyphenated kiwis share an instant wink and nudge in our collective understanding of a particular phenomenon. So for instance when ten years ago A Thousand Apologies went to air, although pan-Asian in content, the Lebanese and Brazilian communities loved it. Certain moments of exclusion or certain moments of embarrassment or humiliation or familial obligations and pressures connect with many immigrant cultures.

M Because you go to and from India and New Zealand and you were educated in the States as well, do you see yourself also as a global citizen as much as a citizen of New Zealand or India?

Shuchi To the extent to which that is allowed. It’s all very well for me to think of California as my third home, in my own head. But since Trump I don’t feel warm and fuzzy about being in America. I still go there a lot for work, and to visit friends. But I don’t feel any joy standing at LAX immigration having to identify myself as this or that.

I’m working on a feature-length animated film set in Japan. I’ve been traveling to Japan a lot lately. I just love it. I’m discovering so much, learning so much, and have begun to feel this huge attachment to the place. Because I love it so much I practically don’t want to finish writing the screenplay because then I won’t be able to justify being back so often. So I think there is a certain amount of curiosity or wonder, a kind of nomadism that I’m very aware is also privilege. You know it’s not I’m truly homeless, of course not. But I don’t feel that my identification is my nationality or my ethnicity. It’s the connections you have with people and places across the world.

M So how did you connect to Japan?

Shuchi I was a big fan always of Miyazaki’s films and Studio Ghibli films, always thought they were much more women/girl focused, three dimensional girl characters, rooted in strong ideas of environmentalism, or courage, or activism. I mean it wasn’t until 2013 that Pixar had its first girl protagonist in Brave!And even when they had nonhuman films like Cars the anthropomorphized protagonist was a male car. And the ‘girl’ car only batted her long eyelashes. Even with Toys the protagonists were male toys. Same with Wallace and Gromit (Nick Park’s fabulous claymation films) — one guy and his best buddy male dog.

This gender inequity in American and English animation, combined with my own fandom of Ghibli style animation prompted me to write a screenplay in which a Pixar girl travels to Japan to become a Japanese anime girl. While it celebrates animation, the story is really about bodies and transformation and the kind of message we send out to young women about makeovers. My young protagonist goes get her desired new body but soon realizes that for lasting happiness she needs to transform from the inside. I’ve had the good fortune to work with a script consultant in Tokyo but because we only work with translators it’s all got to be face to face and therefore slow.

M And the work that you do in America?

Shuchi A couple of things.

There’s a documentary that I shot in India on the relationship between fashion designers and artisans. Looking at this argument of sustainability not from solely an economic or green perspective, but in terms of relationships. What makes this industry sustainable are the relationships that are forged between artisans and designers. So my collaborator Katherine Sender, who is a filmmaker and academic at Cornell, and I went to India together. We shot the film in 6 Indian cities/towns and since then Katherine and I keep meeting each other in USA or online to work on post production.

I am my worst enemy. I’m always complaining about being time poor; I get resentful and I think, ‘God, I’d be great to sit on my arse and do nothing’. And yet, instead of finding time to take a beat, something else comes along and I find myself going ‘hmmm, that sounds like so much fun’.

Also I’m eclectic, you know — working across various forms. But there is a thematic connection. If you put all my shorts and features, television work, and my publications in one basket you will definitely see a common thread. I’m always wrestling with the idea of home and belonging, inclusion, exclusion.

It’s in Fleeting Beauty and Clean Linen, it’s in Coffee & Allah, it’s in Apron Strings. It’s in Firaaq, it’s in Thousand Apologies, it’s in A Taste of Place: Stories of Food and Longing — all narratives of ‘difference’ in one way or another. Then sometimes I walk away from that, like I did for this textile documentary, because if I ever had another career in life it would be making textiles. That’s a big love I have. And Katherine, with whom I shared a guilty Monday pleasure of watching Project Runwaytogether, would often tell me if she had a different career it would be in fashion. When she decided to move back to the USA, we hatched this documentary idea to keep our lives threaded together through our love of textiles.

The other reason I travel to the US is to work with the Center for Digital Storytelling (now called Story Centre) in Berkeley, that has existed since the 1970s. I’ve both learnt from, and then co-facilated workshops in digital storytelling with the Center’s staff. Later I tweaked or re-calibrated that model to suit the Pacific context with my longtime collaborator and friend in New Zealand, Sarina Pearson. As a Japanese-Canadian wahine born in Hawaii who lives in NZ, Sarina’s understanding of ‘difference’ has always been nuanced. She also happens to be my colleague at the University of Auckland so we been able to work on various projects together for the last 21 years, including some of films I mentioned earlier.

Lately, we’ve been doing a fair amount of work in the field of digital storytelling with Māori academics, researchers, and clinical practitioners in the School of Nursing. We’ve done a workshop in Kerikeri, one in Napier. We’re coming to Kāpiti soon. It has been a privilege to listen to Māori, often women, speaking of their experiences of whānau care; and customs and rituals around death and dying. This type of work though within the realm of ‘filmmaking’ is also very different. It’s community-based participatory storytelling in which the workshop serves as supportive space within which participants make digital films.

M Do you work with an audience or audiences in mind?

Shuchi Films are capital and labour intensive so there is little point in developing projects without a clear sense of your audience. As I tell my students, a script is a blueprint for something that has yet to be made within an industrial context. An artist can paint just for themselves without ever showing their work to anyone. It’s legitimate — the sketch in an artist’s book is their completed work. But most architects design or sketch buildings that are yet to be constructed. Screenwriters write screenplays knowing these are first links in a long industrial chain. You can make a living in the USA optioning screenplays that never get made, but their intention is always to see it fulfilled as a film. Feature writing is a long road and can take something out of you so if I’m not interested in the audience, then I’d rather write in my journal. Of course audience awareness should not be conflated with pandering to an audience.

M So who do you see as the audience for Shit One Carries?

Shuchi For this type of short it’s different. No one recovers the money they spent on a short film. They are for mana, professional development, or experimenation. You always have some sense of your audience — it’s good to ask what you want to achieve through the short. A festival short may attract a different audience than a short that’s uploaded on Youtube. Festivals attract film buffs that are aware of cinema traditions, cinema history, film grammar.

For some filmmakers this kind of festival screening is calling card to be taken seriously as a director. I didn’t make Shit One Carriesto signal myself as a feature director. So while I did care about NZIFF selecting the film, my main focus was making the best film I could make, learn something amazingly new, make myself supremely uncomfortable by taking on something I don’t normally do and hopefully do it well enough that an audience connects with it. And that connection is really all I was seeking.

During the festival screenings people laughed at so many points in the film, including groans when they were faced with actual shit. If you understand Gujarati then the film works in additional layers. We had a screening at the Auckland Art Gallery and there were about 75 Indians in that room and it was just loud and crazy because they got the Gujarati. It’s a subtitled film and it loses a fair bit in translation. That could just also be because of my limited skills in subtitling. But those who understand the language definitely get a lot more out of it.

M What do you see as the challenges for women screenwriters and directors in New Zealand at the moment, for women in general and in particular for women filmmakers of colour?

Shuchi It has been historically hard for women directors. And then it’s that much harder for women of colour. I mean I wish it weren’t and I wish that the narrative was different but it’s just not. So sure, at some level in New Zealand all filmmakers struggle to create their own IP. Small country, small market. But at the same time, there is something systemically faulty if after Merata Mita’s Mauri (1988) the first wāhine Māori-directed feature film is Waru in 2017. Look at the woeful statistics published by New Zealand on Air about Asian creatives. I’m just gobsmacked. We definitely need a public service broadcaster so that certain narratives that ostensibly do not have market value are given an opportunity to find or create an audience. That audience IS out there. It’s us.

M Are things changing?

Shuchi We are pushing for change. Very volubly.

Selina Joe, Roseanne Liang, Gilbert Wong and I have formed an organisation called the Pan-Asian Screen Collective (PASC). We are a training and advocacy group representing 400 Pan-Asian screen practitioners. We want to increase pan-Asian representation onscreen and behind screens. We’ve received funding from NZFC for which we’re truly grateful but a big part of our job is to constantly lobby for equitable opportunities for our members BUT also point out structural blind spots within a system that lets these inequities flourish in the first place. And that troubling word ‘diversity’. Diversity on screen is not about ‘showing different people’ — it’s about the level of inclusivity in an organisation or an environment or within systems of power.

M The system is flawed...

Shuchi We have to ask, not wait to be given. As women we have to work collectively, as POC women we have to work collectively. Somebody in LA once said to me, ‘All your work has been with women directors. Please tell me you hired them because they were talented and not because they were women’. Despite being really pissed off I was able to retort with, ‘Would you ever ask me this question if I’d worked with six men?’ Even the people who call themselves liberal and open, even they end up perpetuating this gender-biased system. We all know that it’s no joke that a white guy can make two terrible films and still be hired to make a third one.

M And those situations are compounded for Asian women?

Shuchi In the New Zealand context, because we rely on public funding, it’s doubly complicated for Asian creatives. You could get stuck between a rock and a hard place. For some stories you get ‘Yeah, but how can you make this work for all New Zealanders?’ Whereas for other stories you may get, ‘Yeah, but what’s Asian about this? We’d like you to use your voice’. As an Asian do you always have to perform your Asianness? Who decides how Asian something really is? Or what does ‘all New Zealanders’ mean? We have a lot of work to do.

M What is your screenwriting regimen?

Shuchi I’m a full-time an academic therefore teaching always has priority over everything else. My screenplays and films are part of my research programme. This also gives me the opportunity to write spec scripts. The only caveat is that I have to fit that around teaching/semesters. I think teaching screenwriting keeps me sharp about my own craft. I’ve always enjoyed it, being in a classroom and wrestling with students’ stories, especially genres in which I don’t write. For instance, my students interested in genre force me to consider tropes of horror or sci-fi.

Of course there are times when I fantasize about being a full-time writer. In lieu of that, I create immersive situations in which I can lock myself up and write without distraction. I’m not good at writing for an hour here and half hour there. Writing in hotel rooms, on silent writing retreats — that type of regimen suits me perfectly. That’s what I did with Katherine in San Jose recently. One week we sequestered ourselves in a hotel to work every day from 9:00 to 5:00. No phones, nothing.

M Do you have children as well?

Shuchi No. That’s a decision I took many many years ago. When I decided to do film and work in different parts of the world, I couldn’t imagine doing that with children. My mother gave up her career to raise us and whether she meant to or not, it set some kind of bar for me. When in doubt, blame ma! I’m joking. I love other people’s children and I love being an auntie but I haven’t regretted not having my own. I know what I’m missing. I’m not blind to that. But no, I don’t regret it.

M That’s a wonderful model for people to have out there isn’t it? I think a lot of women are very frightened by that decision.

Shuchi Then there are the Vanessa Alexanders of the world who raise five beautifully talented children while writing, producing and directing television AND ride bicycles across dubious cross country tracks. I think we need to create an environment in the film industry for women so that they feel just as comfortable having children as they do about wanting a career, without compromising either.

UPDATE

Since this interview was recorded, Shuchi has joined Kerry Warkia and Kiel McNaughton, producers of Waru and Vai, to produce Kainga, the third film in the trilogy — this time with 8 Pan-Asian women directors exploring notions of home.

Shit One Carries continues its international festival journey and recently won the award for Best Regional Film at the 10th Gujarat International Film Festival, in India.

Shuchi, Sarina Pearson and Peter Simpson have collaborated on a documentary shot in the western Indian desert, The Rann of Kutchh, currently being edited by Prisca Bouchet.

Elder Birdsong, an animated short film by Shuchi and Sarina (funded by Te Arai Palliative Care Research Group) is being premiered at the Show Me Shorts Film Festival.

The Pan-Asian Screen Collective is being heard — there was a record number of Pan-Asian applications to the latest round of NZFC short film funding.

Comments

Post a Comment