Introducing The Complex Female Protagonist Roars

This year, I got a stall at the local queer fair Out in The Park, to sell my neonics-free bee-loved flowering plants, another artist's beautiful work and this cap, which I had made in New Zealand from a design by the Bluestocking Film Series, thanks to its director, Kate Kaminski. The fair was postponed – Wellington wind – so I distributed some caps to family and Facebook friends. I’m delighted that the new owners tell me stories about when they choose to wear the caps, how they feel wearing them, the responses of those they meet when wearing them. Wearing a cap with the Complex Female Protagonist slogan has many effects. I love it.

Last year, when I wrote Get Your Hopes Up, near International Women’s Day, I recalled what David Mamet wrote, about drama being about the creation and deferment of hope. This year, because of those caps and the stories their owners tell me, my mind and heart are on the Complex Female Protagonist. So I’m writing three posts. This first post moves on from hope, to explore some characteristics of the the delightful collective Complex Female Protagonist-working-for-change-in-long-form-screen-storytelling (henceforth 'the Activist CFP'), from as much of the globe as I can access. Who is she, right now – the informal and ever-changing collective of activists who work to increase the volume, diversity and quality of screen storytelling by women writers and directors, often focusing on women and girls?

And why does this Activist CFP ‘roar’? I’m thinking back years, to the first time I found CampbellX’s BlackmanVision website and its header ‘When the Lioness Can Tell Her Story, The Hunter No Longer Controls The Tale’. Today the lioness roars without cease, thanks to the Activist CFP.

In the second post, I’ll write about equity and public funding for screen storytelling, with reference to the research I’ve done on women’s film funds and women’s studios. That’s because I’m in New Zealand, where, thanks to Jane Campion’s commitment as a member of the national Screen Advisory Board, the New Zealand Film Commission will today announce its very first gender policy. Yes, we’ll roar anyway. But we’re entitled to an equal share of taxpayer funding to do that.

The third post considers what might happen if we have equal numbers of screen stories by women and men. In New Zealand, (white) women poets now publish as many books of poetry as men do. How did this happen? What effects does it have?

The collective Complex Female Protagonist who works-for-change-in-long-form-screen-storytelling (the Activist CFP)

If I think very very hard I can just remember the women’s film activism of a decade ago, when I started to work on my New Zealand-based PhD that became the Development Project. There wasn’t much of it. For instance, Melissa Silverstein hadn’t started Women & Hollywood, that steady beat of information and inspiration since 2007. There were lots of women’s film festivals. But their (our) online presence was quiet. The academic work around women and film was remarkable for its lack of hard information and its disjunct between theory and practice.

|

| A view of the Activist CFP roaring: Kate Prior (writer/producer) and Abigail Greenwood ‘share’ their Best (New Zealand) Short Film award |

And the next generation just gets on with it, like the Candle Wasters – Sally Bollinger and Elsie Bollinger, Minnie Grace and Claris Jacobs (aged 17-21) who have produced an astonishing 76 episodes of Nothing Much To Do, a YouTube webseries inspired by Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing, and have a new series coming, Lovely Little Losers, inspired by Love’s Labour’s Lost.

Last year, when I got my hopes up for lasting change, I was uncertain that it would happen or how iot would happen. But this year the Activist CFP has blossomed, in a chaotic context that embraces Hollywood, quasi-Hollywood and the rest-of-the-world– both independent and state-funded, where there are some interesting overlaps for everyone involved in film-making (for instance, many of the same nominees featured in the Independent Spirit Awards and in the Oscars). Furthermore, partly because we have so many personal devices for viewing, ‘the feature film’ for theatrical release is much less dominant than it was, in the mash up of long-form screen storytelling across feature films, telemovies and episodic work that includes webseries, multi-director tv series and single director tv series. Only the over-40 audience for theatrical viewing of American films grew in 2014, according to the MPAA, and the audience under that age shrank. At the same time, ‘the women’s’ audience and other so-called minority audiences continue to grow in strength, as Brook Barnes explains –

At a time when so many movies turn themselves inside out trying to attract everyone (a plan that could be summed up as 'wide and shallow' in industry parlance), it is clearly possible to fill a big tent by picking a couple of demographics, in particular underserved ones, and superserving them ('narrow and deep').In this context, as Ava DuVernay, writer and director of Selma, arguably a superserving feature, but one that attracted a 'wide', multi-demographic audience inside and outside the United States, has said–

The gatekeepers’ gates are rusting. There are new ways to do things, new ways to shoot. New ways to monetize, new ways to distribute, new audiences to find, new ways to communicate with them. These new ways don't require some old man telling you, you can do it. Now that that's the case and we know it's the case, we need to begin.So, in a southern summer and now early autumn of listening to, watching, reading and thinking about the Activist CFP, what’s struck me most about her present characteristics and her response to all this? I love her because she's diverse: she flows across across geographical, cultural and professional boundaries (and the rest!) and generates many remarkable Alliances. Above All, she's Active, as befits a Protagonist. All Over The Place. Just look at that group of women adding women filmmakers to wikipedia!

Generous women adding women filmmakers to Wikipedia–@IAmJenMcG @deconstructjg @BiatchPack Tx @emilybest! #womeninfilm pic.twitter.com/nAiu3L7ksr

— Marian Evans (@devt) January 11, 2015

The Activist CFP's dialogue is characterised by vitality, informed by statistical data. She has Hollywood-oriented strategies. She has independent filmmaker strategies. She's doing interesting things in television, with not a lot of visible crossover with film activists. And she includes actors. Last year I celebrated actors who direct and this year I've noticed that more actors are becoming producers and I want to celebrate that and inquire about its effects. The Activist CFP includes women cinematographers, whose eyes frame women especially well. From the breadth and depth of this global consciousness-raising I'm now much more certain that change will come. And the Activist CFP's greatest strength, I suggest, comes from women filmmakers of colour. In particular, watching and listening from a distance and with limited sources of information, it seems to me that African-American women are getting their stories onto screens by working with imagination, tenacity and integrity and best practices that the rest of us can learn from.

Alliances

|

| Film Fatales at Sundance photo: Destri Martino |

An invitation is not enough: powerful organisations where there is systemic inequality have the responsibility to research and reach out, and to create change within the structure so that it is welcoming to diverse participants.This principle is fundamental to making change for women and for the diverse groups we’re part of and that systemic inequality profoundly affects. So, not surprisingly, among the 70 signatories to the letter are women who may disagree with one another about why women write and direct too few films and why too few films adequately represented women and girls among their characters.

But they (we) came together as signatories because they (we) knew that making this kind of public statement is an essential strategy for change. On the list are writers and academics, film festival directors and programmers and some courageous filmmakers (I understand that a number of directors declined to participate). Signatories include grandes dames Laura Mulvey, whose celebrated Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, back in 1975, called for a new feminist avant-garde filmmaking that would rupture the narrative pleasure of classical Hollywood filmmaking; and Debra Zimmerman, since 1983 executive director of Women Make Movies, founded in 1969. There’s Thuc Nguyen of The Bitch Pack and The Bitch List; Ellen Tejle of the Swedish A-Markt/A-Rating for films that pass the Bechdel Test (now joined by the Bath Film Festival's F-Rating, which extends the test from what happens onscreen to those who have made it happen); Melissa Silverstein; Beti Ellerson of the Center for the Study and Research of African Women in Cinema; and Bérénice Vincent and Delphyne Besse of France’s Le Deuxième Regard. And many more. A beautiful mix, to be celebrated.

Then, earlier this year, Marya E Gates announced her A Year With Women–

In 2015, every movie I watch (at home or in theaters) will either be written by, directed by, co-written by or co-directed by women.

This set off a flurry of world-wide enthusiasm and idea-sharing in the activist twittosphere. This led to Maria Judice’s Rewrite Hollywood, which links to a woman-written script each week and to further synergies with projects like The Bitch List, The Director List (with Destri’s beautiful new site coming soon and her new Instagram) and #DirectedByWomen, a global celebration happening later this year. And when the second Rewrite Hollywood script went up, Of Love & Basketball, its writer and and director Gina Prince-Bythewood tweeted–

LOVE & BASKETBALL script via REWRITE HOLLYWOOD & @oldfilmsflicker http://t.co/QQxFESnsoc (loved visual of opening in script but not in film)

— Gina PrinceBythewood (@GPBmadeit) January 23, 2015

What a fabulous, sisterly, response to have as part of the conversation! Then there’s Shaula Evans’ site. ‘Inspiration and support for writers’ is her modest introduction. She’s super-skilled with scripts and at creating a diverse community, generous, sharp and funny and I’ve treasured her contributions to this blog, in the Real Talk About Implicit Bias tab. Women are an important part of her community and her latest alliance, with Lexi Alexander, Miriam Bale and Cat Cooper , created the #FilmHerStory hashtag, and inspired responses from all over.

Need story ideas? We have 300+ on our #FilmHerStory @Pinterest for women who deserve biopics! http://t.co/LSLBMfET79 pic.twitter.com/1Tloj9gcVi

— Shaula Evans (@ShaulaEvans) March 8, 2015

In another example, at a regional level, in Canada the St John’s Women in Media Summit’s powerful Communique, developed by Women In View, came from strong organisational alliances among its signatories. Notable on the list are Canadian Women in Film & Television (WIFT) chapters.This signals another hopeful sign of sisterhood — and some brotherhood — across organisations that in the past didn't collaborate. And the communique’s recommendations provide a kind of manifesto for diverse women in film, in all countries where the state funds film.And at this year's Berlinale, the organisation Pro Quote Regie staged a stunning intervention, supported by an exciting website, seeking gender equity in funding. Even Margarethe von Trotta participated!

Belinde Ruth Stieve wrote about the group in English, here.

And in a totally personal pleasure, I just had an email from the Seoul International Women's Film Festival. This year, they have a programme that focuses on recent Swedish women's cinema and they'd like to reproduce my interview with Ellen Tejle about the A-Rating. Lovely to feel a Korean-Swedish-New Zealand Activist CFP connection.

All these alliances – and many more – contribute to Activist CFP vitality that's informed by multiple sources of hard data, by carefully considered strategies for making change in Hollywood, by independent filmmaker strategies, often fuelled by crowd-funding, by change and solid achievement within television and change within a range of organisations. It's a delight to be a tiny participant in this continuous brainstorm and hard work, an intellectual and emotional climate change. I treasure the action and the drama it generates.

Data

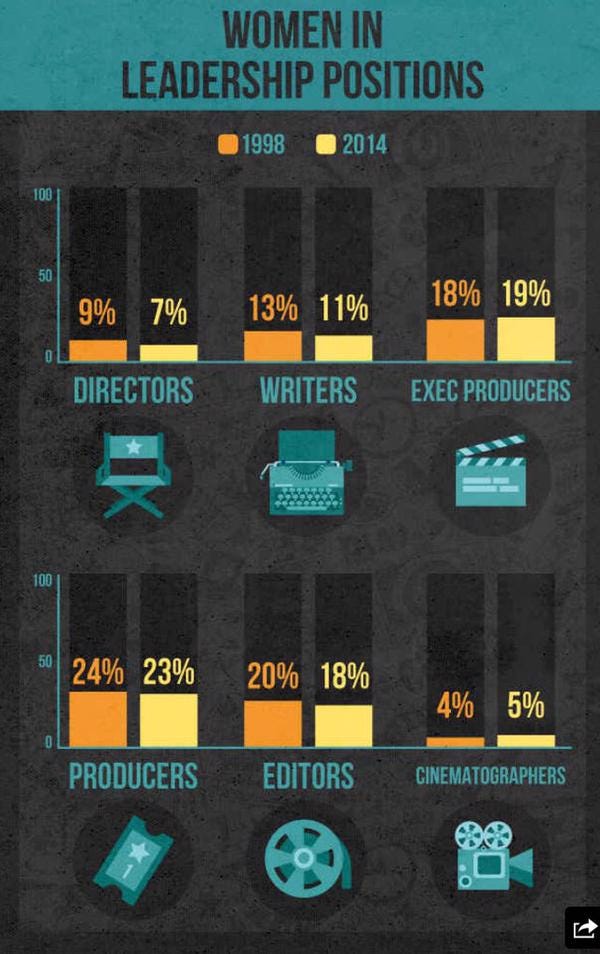

The vitality of the Activist CFP's debates, especially about films by and about women, is informed by quantitative gender data that continues to roll in. Some of the data, for example from this Martha Lauzen infographic, shows the general picture in those crucial-to-many United States Top-Grossing 250 features, which colonise those of us who live outside the States – in 2014 72c/ $1 that the best-earning films earned came from outside the United States and Canada, up from 70c.  |

| Martha Lauzen infographic |

I'm thrilled that at last there is lots of data. I’m longing to know more about Asian, South American and African countries but for now in Europe, for the first time, we have the comprehensive European Audiovisual Observatory research. In New Zealand for the first time we have official gender data, published by the New Zealand Film Commission, the state funder here. Until there's reliable in-depth data from everywhere, blogs like Beti Ellerson’s African Women in Cinema are handy. In just one example, Beti recently interviewed academic Zélie Asava – who has also worked as an actor, journalist, in politics and as an equal opportunities consultant – on her research into mixed-race identities and representation in Irish, United States and French cinemas.

And because there’s now so much data and that so consistently show that it's problematic for women who write and direct and for those of us who want stories about women and girls, the debates seem to have shifted a little, to focus more on problem-solving, strategies for change and how to implement them. Because of this, it’s become essential to distinguish between entrenched ‘Hollywood’ practices and the strategies and practices of the independent rest-of-the-world, whose films probably don’t have big marketing budgets and don’t often appear in that United States 250 Top-Grossing Film list. When they do, it seems to me, it is usually because they’re on that fluid boundary between Hollywood and the-rest, because of a project-specific connection, through some kind of co-production investment or because a major distributor has taken a punt.

Hollywood-Oriented Strategies

‘Hollywood’-oriented strategy, often generated through debate about those Top 100 or 250 US features, is diverse. And needs to be, if change is going to happen. Behaviours and strategies explored – and NOT explored in Manohla Dargis’ conversations with Amy Pascal, formerly head of Sony and Hannah Minghella who is also at Sony, have different emphases than those expressed by theory-oriented and number-crunching activist academics like those in Stacy Smith’s team at Media, Diversity & Social Change Initiative at USC Annenberg, who often research for the Geena Davis Institute. After Manohla Dargis received reassurances from Amy Pascal and Hannah Minghella that they wanted to hire women directors, she records that ‘[Ms. Minghella] and Ms. Pascal were sincere, but good intentions don’t mean much when the six major studios consistently do not hire women even for smaller movies’ – the discussion did not include description and analysis of the studio strategies for increasing the numbers of women directors they hire. And the research team’s suggested strategies may reflect Geena Davis’ ideas, like this one, aimed at all those who write, and is part of cherishing the presence of women and girls in the world–

Step 1: Go through the projects you’re already working on and change a bunch of the characters’ first names to women’s names. With one stroke you’ve created some colorful unstereotypical female characters that might turn out to be even more interesting now that they’ve had a gender switch. What if the plumber or pilot or construction foreman is a woman? What if the taxi driver or the scheming politician is a woman? What if both police officers that arrive on the scene are women — and it’s not a big deal?

Step 2: When describing a crowd scene, write in the script, “A crowd gathers, which is half female.” That may seem weird, but I promise you, somehow or other on the set that day the crowd will turn out to be 17 percent female otherwise. Maybe first ADs think women don’t gather, I don’t know.Other strategies appear in the context of legal issues at the American Civil Liberties Union’s Tell Us Your Story project, as it collects their discrimination stories from women directors, in the work of courageous analysts and directors like Lexi Alexander and Maria Giese and from contributors to blogs like Bitch Flicks and Women & Hollywood, whose founder Melissa Silverstein also founded the Athena Film Festival as a strategy for change.

Independent Filmmaker Strategies

Ideas and strategies developed by independent filmmakers sometimes intersect with the ‘Hollywood’-oriented strategies, but are generated by individual filmmakers’ overarching desire to tell their own stories. For a long time now, independent filmmakers have refused to wait for ‘Hollywood’ to change. But I think their work is infused with new energy. Partly because we now have crowdfunding, a simple, effective strategy we can all embrace.

Crowdfunding's helped many women’s films that have done well in the States over the last year (just wish more reached New Zealand), like Jennifer Kent’s Babadook, Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night, Afia Nathaniel’s Dukhtar. This is how actor/ director/ editor Josephine Decker explains the value of crowdfunding and why it’s a significant element it getting women’s stories to the screen–

I make these movies for low budgets because I’m just terrified of big ones and all the sucking up and accommodating that those enforce, but crowdfunding helped me realize that you can fundraise from people who believe in you, and want you to realize exactly the thing you want to make.I hope that 2015 will be the year that more people support more crowdfunding projects, because films like those I’ve mentioned show how worthwhile it is to invest the price of a ticket in diverse women’s work. It doesn’t just help them do the work they want to. It also helps them build their audiences, essential given most women’s lack of access to funds for marketing. For those of us without time to research current crowdfunding campaigns, indefatigable filmmaker and activist Destri Martino curates a list of current projects on her Twitter account each week.

Josephine Decker is typical, I think, of independent women filmmakers. She released two features in the last year, Thou Wast Mild and Lovely and Butter on the Latch and is about to crowd fund for another project. In a story by Paula Bernstein (like Manohla Dargis a consistent source of excellent writing about women filmmakers) Josephine articulated her philosophy–

Being an independent filmmaker was never a great way to make a living, and that hasn’t changed, but the skills that you gain from pursuing your own vision can lead to a lot of opportunities. Because of my two features, which may or may not make me money, I learned in a profound way how to see a story through from beginning to end, how to tell a gripping story, how to edit, how to oversee a crew, how to work with actors and how to spread the word about a project. Currently, I am prepping a big media campaign with a national non-profit, am pitching a web series, just got a Kickstarter funded to make a dream film and am pursuing my next feature with a lot more ammunition in my giant balloon playpen. So — I would say: Do I have a lot of money right now? No. But — if it’s possible to balance your own projects with some paid work (and technical skills of filmmaking are something people will pay for), then making your own features is a great way to invest in a future in which you DO get paid to do cool shit.Television

And also, honestly, I love making films for no money. We live in a culture of film as a business. I don’t know if transcendent artists generally emerge from a commercial model. To be a great artist, you have to be willing to take risks and to do things that no one would ever pay you for — at first. I am happy to be living a spiritually rich life in which filmmaking is a gigantic pleasure. And of course, this pleasure would be more pleasurable and less stressful with money at the table, but maybe writing all this is making me realize I am a little bit terrified of having actual money invested in my projects because I worry it will distort my vision and the very deep thing I am aiming for when I get actors in a room and start improvising.

Late last year, when she accepted the Sherry Lansing Award, Shonda Rimes asserted (see clip below) that the glass ceiling in Hollywood has gone. There’s truth in her assertion, reinforced — at least in television — by the reality that during 2014 ShondaLand dramas supplied the entire lineup on ABC primetime’s Thursday night and by marvels like the latest Golden Globes list of nominees for the Best Television Series — Musical or Comedy. Women created four out of five of those diverse nominees– Jenji Kohan’s Orange is The New Black, Jill Soloway’s Transparent, Jennie Snyder Urman’s Jane the Virgin and Lena Dunham’s Girls. Further evidence comes from this tweet, which highlights both the fine quality of women directors’ work in television and the reality that, for whatever reason, women directors are not well represented there.

DGA TV DIRECTING AWARDS: in the top two categories, comedy and drama, women (who direct only 14% of TV shows) made up 50% of the nominees!

— Maria Giese (@MariaGiese) January 24, 2015

Lily Loofborouw’s recent article, TV’s New Girls’ Club also celebrates this television achievement She writes about shows that are ‘for the most part created by women and center on female characters’ and suggests that these shows defy ‘what has come to seem like a glib bleakness in highbrow programming’–

If The Sopranos started the age of the antiheroes, these shows mark the dawn of promiscuous protagonism: a style of television that, rather than relying on the perspective of one (usually twisted) character, adopts a wild, roving narrative sympathy…and treat gender as a curiosity rather than a constraint.I recognise and love ‘promiscuous protagonism’ because in the past I've tended to write multiple protagonist screenplays and learned from other women writers that they too are more likely to do this than the men writers we know. And where better for promiscuous protagonism than on television?

Meanwhile, change is in the air in some organisations where women and men have become activists for change onscreen.

Organisational Change

With some exceptions (in Sweden, for instance), until recently, many chapters of Women in Film & Television International appeared to focus primarily on their remits to ‘stimulate professional development and global networking opportunities for women’ and to ‘celebrate the achievements of women in all areas of the industry’. The organisation’s more radical aims are internationally focused, like the one to ‘develop bold international projects and initiatives’. But more and more, WIFT chapters ally with other local organisations to work for change. WIFTUK, for instance ‘collaborate[s] with industry bodies on research projects and lobb[ies] for women’s interests’. Women in Film in Los Angeles collaborates with Sundance Institute on its Women’s Initiative. In New Zealand, WIFT – I understand – worked on the gender equity policy at the New Zealand Film Commission, the state funder. That’s all awesome.

In Britain last year, the British Film Institute (BFI) established its ‘three ticks’ diversity policy, ‘designed to address diversity in relation to ethnicity, disability, gender, sexual orientation and socio-economic status’. Producers who apply to the BFI for funding must producers who apply must demonstrate their commitment to encouraging diverse representation, across their workforces and in the portrayal of under-represented stories and groups on screen. And Britain’s Channel 4 reaffirmed its historical commitment to diversity.

Late in 2014, the World Conference of Screenwriters international guilds and screenwriting organisations, including the very powerful Writers Guild of America West, passed the ‘Women’s Resolution’–

Statistics from writers’ organizations around the world show clearly that women writers are under employed. We write fewer scripts, receive fewer commissions, have shorter careers and earn less than our male colleagues. Women have the talent, experience and ambition to participate as equals in every aspect of the industry. What stands in our way is institutional gender bias. We the 30 guilds and writers organizations present at the Warsaw Conference of Screenwriters 2014 representing 56000 male and female screenwriters, call upon our commissioners, funders, studios, networks and broadcasters to set the goal of having 50% of scripts across genres and at every budget level to be written by women. (my emphasis)At the same time, the Swedish Film Institute continues to set the standard for other state funders and the European Women’s Audiovisual Network goes from strength to strength, with close connections to Eurimages, the pan-European funder as well as to the wonderful cohort of Spanish women directors whose drive ensured that EWA was established. I'll write more fully about state funding in the next part of this series.

I bet there’s lots I’ve missed. Awareness has grown, commitments are being made and action is being taken. Yes! And some of all that’s happening among actors too.

Actors

Late in 2014, the LA Times brought together an 'Oscars Round Table' group of actors – Jennifer Aniston, Emily Blunt, Jessica Chastain, Gugu Mbatha-Raw and Shailene Woodley. I love these round tables and the way the videos and the partial transcripts are edited – bits that I find interesting are often dropped from one or the other and I tracked to and fro with this one to learn the most I could about (these) actors as an element of the Activist CFP. In a couple of places I've cobbled together quotes from the incomplete video and the incomplete text.

I'm always excited when actors write and direct. There are lots and lots who do this and in general they do it so well. This year, I've noticed them as producers: two of the actors in this group, Jessica Chastain and Jennifer Aniston, as well as Reese Witherspoon, Oprah Winfrey (a unique example!), Lupita N'yongo, Angelina Jolie, Jodie Foster. Some of these women have been producers for years, but I wonder if the numbers and volume of actor-producer films have increased because of the 'new ways to do things' or because it's become easier for women who act to raise money for projects that they appear in, either as protagonists or in smaller parts. In response to a question about successful films with women as lead characters, Jessica Chastain (who played the central character in Kathryn Bigelow's Zero Dark Thirty) says–

To me it's not a surprise any more. it's a fact. Women perform great at the box office. Audiences want to see lead female characters.And then, in response to another question about what it would take to change the gender proportion of speaking roles (currently 2/3 men) she said–

Women writers. If you look at the studies, female writers and directors are non-existent. The percentages are really small. I think we just need to encourage girls in high school and middle school that they can be anything they want to be and if they want to be a film director they can do that, if they want to be a writer they can do that. We need more points of view... Also we need more support for women directors and writers in the industry.Jennifer Aniston's response placed responsibility more squarely on 'the industry' rather than the education system and individuals–

You hit the wall right at the top. If there's a female writer being suggested to do a rewrite on a script, it's always the big boys going 'Let's go with the [man]'.(And if you doubt this, take a look at this Sony email from those circulated a while back–

Men wrote and directed projects that Jessica Chastain and Jennifer Aniston produced, with the exception of the Jennifer Aniston-produced TV movies Five and Call Me Crazy, exploring the impact of breast cancer where women storytellers predominate although some men were also involved in writing and directing. It's impossible to tell from the round table why male writers and directors were otherwise the default choice. All the projects Jessica Chastain has produced have one writer/director, Ned Benson, for whom she produced a short film before The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby trilogy. She read the Eleanor Rigby script early on and says–

It's a lot more work [producing] but the good thing is you get to surround yourself with people you believe in. I made Eleanor Rigby with all of my friends, a first-time writer/director. So it was a really really beautiful experience to see my friends go through that journey and have that success and I learned so much doing it.Jessica Chastain's producer story reminds me of what happens in New Zealand's 48 Hours competition, where friends work together and very few women direct. When a mixed gender group of friends work together on low-budget projects does a male writer/director tend to be the default choice? Have no women approached Jessica Chastain to produce their projects and is this why she thinks there are so few, although it's so well documented that there are many? And has Jennifer Aniston chosen men except on the breast cancer projects because she needed them to attract investors?

|

| Emily Blunt, Jennifer Aniston, Gugu Mbathe-Raw, Shailene Woodley |

I myself have been really fortunate in the last year or two to work with three female writer/directors. They provided me with my first big roles on screen, so in terms of point of view and three-dimensional complex characters, I have women to thank for that and the layers and the nuances they bring to the writing and to be driving the story and not just an adornment.The interviewer asks her if she can tell the difference if a woman writes and directs and she affirms that she can, in her 'limited experience' and then after Jennifer Aniston interjects 'You're spoiled' and everyone laughs, Gugu Mbathe-Raw acknowledges 'Yes, I guess I am spoiled, especially as I say with Belle and Beyond the Lights and written by women too, it's just that the focus is that much more three-dimensional on the woman's role'.

Yay, I went to myself, as I listened and watched. And it got even better. For the first time I can recall that women actors discuss women cinematographers in this kind of public and group context. The interviewer asked Jennifer Aniston, whose Cake had a woman cinematographer, Rachel Morrison, 'Do you think it makes a difference when there are more women on the production team?'

|

Rachel Morrison, DP for Cake

|

G M-W We had a female DP [Tami Reiker] in Beyond the Lights as well and she was operating the camera and, again, her perspective, and the intimacy I think, that quiet energy—

JA They get into bed with you and the camera’s right here [she indicates up very close], incredible.

|

Tami Reiker, cinematographer for Beyond The Lights

|

Women Filmmakers of Colour

The Activist CFP is autonomous. Self-determination is her motto. Very often she also exercises her sovereignty as a storyteller. And if she wants to get her stories on screen and to an audience, that activity – on its own – is immensely demanding. Not surprisingly many of us find it necessary to abandon activism (of itself creative) just to get the stories out there. And necessary to distance ourselves from serious activism because it may compromise our access to resources to make our work.

But is that truly necessary? Is there an effective way for the Activist CFP to integrate her creative work with her activism? I’ve decided that it is possible. Jane Campion, for instance, continues as a rare high profile screen storyteller and Activist CFP. And women of colour are doing it too, especially African-American women who live in the United States, in closer physical proximity to Hollywood than the rest of us.

Over the last five years or so, women filmmakers of colour have arguably achieved critical mass, doing whatever they had to do to keep moving forward and distribute their work widely. They've always been around, of course, but because of the web-based information available it's become easier for the rest of us to access their work – though it's still sometimes problematic in New Zealand, for various reasons, including the rating system's cost. Since Ava DuVernay’s first film, I Will Follow (2010), there’ve been so many outstanding releases that have had wide distribution, like Dee Rees’ Pariah; Haifaa Al Mansour’s Wadjda; Amma Asante’s Belle (her activism is also inspiring and I'll refer to it in the next part of this series); Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night; Afia Nathaniel’s Dukhtar, Gina Prince Bythewood’s Beyond the Lights. (My favorite project-in-the-making from 2014 is Jacqueline Kalimunda's Single Rwandan Seeks Serious Relationship, being made between Rwanda, Paris and the United States and I love the generous vitality of Glasgow's Digital Desperados – thanks for the headsup, Kyna Morgan).

These films are not formulaic Save-The-Cat or Disney stories. They’re heartfelt and rigorous cinematic inquiries. Selma’s about leadership and radical change and community. Beyond the Lights and Belle explore ideas about power and how women of colour are framed. Wadjda and Dukhtar investigate ideas about being a mother and being a daughter. A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night plays with genre. Because of our new, larger capacity to access the work, because of the story choices and because of the strengths of the storytelling, it feels like there’s a shift from 'If we don’t tell our own stories no-one else will' (which always reminds me of Mira Nair's Maisha Lab, a non-profit facility for young directors in East Africa) to a new truth: 'We'll tell the stories we choose and tell them better than anyone else, and we will get them to audiences, who are hungry for them'. This has to have a run-on effect.

And the works I've mentioned are not one-offs. For instance, Dee Rees' telemovie, Bessie (Smith) is out on HBO next month. Ava DuVernay has multiple projects on the go, on various platforms, including a television series she's co-creating with Oprah Winfrey, based on Natalie Baszile's novel Queen Sugar. Ana Lily Amirpour is on to The Bad Batch, a dystopian love story set in a Texas wasteland, produced by Megan Ellison’s Annapurna Pictures and Vice. I love it that Haifaa Al Mansour’s next will be A Storm in the Stars, about the love affair between poet Percy Shelley and 18 year old Mary Wollstonecroft ‘which resulted in Mary Shelley writing Frankenstein’ (!).

(It interests me that in the United States, African-American women’s work seems to be represented more strongly than work by Latinas and Asian-Americans. I’m intrigued that in France, the most prolific film-making country in Europe, where many people of colour live, there appear to be few films by women of colour. I wish I knew more about women of colour working in languages other than English. I long for new features from Maori and Pasifika women. I wish for more films by and about queer women in their diverse communities, told by queer women of colour, like CampbellX’s Stud Life, as well as Pariah and Pratibha Parmar's doco Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth.)

So how do (some) African-American women manage so well to integrate their storytelling with their work as Activist CFPs? And what have I learned from them? Ava DuVernay's speech at SXSW (below) set me off on this section. I watched her talk about paying attention to our intentions, say 'Open up and make your intention be beyond yourself. Because if your dream is only about you, it's too small'. I listened to her speak about going into Selma with the intention of serving the story, heard her add 'I invite you to go inward and see what happens with an intention of service'. And I thought Yes! Activist CFPs are service-oriented; I think that every one of us has a dream for stories by and about women and that dream isn't just about us as individuals. And then I thought BUT. BUT an awful lot of Activist CFPs who are writers and directors aren't getting their screen stories out there to audiences. Certainly we're not doing it as often as Ava DuVernay and her African-American peers. What can I learn from them about combining CFP Activism with getting the artistic work done?

My perspective's limited by what I've been able to learn, of course. By who I am, a privileged white woman living in New Zealand. I'm an 'outsider' engaged in an investigation into how to combine screen storytelling with activism to create and sustain conditions where work by women artists flourishes and reaches wide audiences. From this multi-dimensional distance I may be utterly mistaken in everything I write about African-American women storytellers whose work I'm most familiar with. But I think that these African-American women exemplify the essence of the storyteller Activist CFP at her most realised and most generous, the richest timbre of the lioness' healthy roar as she tells her story.

Although Ava DuVernay's introduced me to these ideas, because she's so precisely articulated her philosophy alongside putting it into practice, I think there's evidence to support my contention that she's part of a long tradition whose time has come, rather than exceptional. And perhaps the time has come because there are new ways of doing things. By why have African-American women grabbed the moment(s) so effectively? In 2015, I suggest, African-American women's integrated philosophy and visionary work comes from their shared history and experience within a group that has been at least doubly colonised, under-represented and misrepresented on screen – as African-Americans and as women – and from the grief and the love that comes from this and the lived daily exposure to the terrible realities of broken black bodies. And from the inspiration of other visionaries like Dr Martin Luther King. (And I think that the very beautiful programme at New Zealand's recent Maoriland Film Festival may have arisen from similar histories and philosophies, or kaupapa.)

This is not to say that African-American women who are screen storytellers all think and act alike. For instance, I understand that Shonda Rhimes prefers to name herself as a screenwriter, director, and producer, not as an 'African-American woman screenwriter, director and producer'. Ava DuVernay calls herself 'a black woman filmmaker'.

And I imagine that when she calls herself a writer, director and producer without other descriptors, a person who creates content about anyone and anything, Shonda Rhimes is, like many other women artists, refusing any limitations. And from within that self-determination she's created new language to describe what she's doing,‘normalizing’ television–

And the two positions are common among women artists in various mediums I think. I remember a version of their presence when David Kavanagh from the Irish Film Board reported to last year’s World Conference of Screenwriters. When a group of women met to discuss his gender and film research and the dismal level of Irish Film Board funding for women’s scripts, there was an ‘angry’ debate. Some women insisted they write ‘differently’ and their scripts are therefore unattractive to producers and funders. Others counter-insisted that they write in the same way that men do. If you're reading this, you're likely to be someone who's decided to choose 'artist (of whatever kind)' or 'woman artist': myself, I'm sometimes one and sometimes the other, or both at once.

So in spite of their differences – and I bet there are many – what seem to be the principles that these women do have in common? I've identified a few that I think are essential to any Activist CFP discussion, especially for those of us who are screen storytellers. I imagine that I've missed a lot, but these are the ones that most affect me and inform my understanding of an ethical and sustainable framework for 'best practice' as Activist CFPs who are also screen storytellers. It's never easy and never will be, but I think these principles are very useful. The first group of principles is about identity: delight in who they (we) are, acknowledgement of where they (we) come from and of the achievement of others in the past and in the present. The second group of principles is about work choices.

Identity Delight

Regardless of artistic descriptor, this seems to be shared. Here’s Shonda Rhimes when she was presented with the Sherry Lansing Award (transcript here)–

Consistent Acknowledgement of Others

Here’s Ava DuVernay after she won Best Director at Sundance, years before Selma was nominated for Best Picture and Selma's 'Glory' won Best Original Song at the Oscars (where she said of the ceremony ‘this is just a room with very nice people applauding. But this cannot be the basis of what we do. This does not determine the worth of my work.’)–

Shonda Rhimes,when she won the Sherry Lansing Award said this about 'breaking through the glass ceiling'–

And of course, if you consistently acknowledge where you come from, you also acknowledge those others whose work is just as significant as yours, right now. Towards the end of her acceptance speech, Shonda Rhimes thanked the women past (‘all the women who never made it to this room’), present and future, who are ‘all an inspiration’.

And here's Ava DuVernay again–

Principles That Affect Work Choices

The first of these is that Hollywood and institutions like government funders (for those of us outside the United States, or who seek state tax credits within the United States) are not that important.

In one interview, Ava DuVernay said this, and I think it may be hard for many of us to hear it, because we have prioritised institutional change–

But it's hard for me to give less attention to institutional change and I suspect it's also hard for many other screen storytellers like me who are Activist CFPs and come from a white woman's place of privilege and entitlement. It's tempting for me to engage with white men's institutions and ways of working, white men's principles, the white male canon and the long long tradition of the solitary artist who's art-making dream is only about himself and involves no service to others at all. The other day, for instance, I read this, from Janet Frame, one of New Zealand's most distinguished writers (Jane Campion adapted her An Angel at My Table)–

I think that one reason why many Activist CFPs like me tend to have Hollywood and state funders as primary reference points is because we believe that if we 'get it right' those white men and the women who work most closely with them will change. Organisations with power will change (and a few have). Or we'll be an exception (and some of us are exceptions and some of us work to hang on to being an exception, as evidenced when women directors voted down a Directors Guild of America motion that would advance women, just today). If we're 'good', those men will let us slip in to join them. Are women of colour, with good reason, less deluded than I've been and and therefore more likely to work 'differently'? I think that's possible.

Take Gina Prince-Bythewood as another example of someone for whom 'Hollywood' is not that important. She is the first woman writer/director I’ve heard assert that she turns down offers of work (from Hollywood studios!), on principle–

Like Gina Prince-Bythewood, Ava DuVernay isn’t going to compromise her vision on the independent route she's adopted. The focus is on doing it, without asking for permission. No complaints about access to funds and other resources. Getting on with it, solving problems as they arise.

Service of Others and The Story

In her SXSW address, Ava DuVernay says that she came by the 'service' principle (and its associated 'Open up and make your intention be beyond yourself. Because if your dream is only about you, it's too small') 'by accident, but now I'm going to try to do it on purpose'. She discusses how with her first feature, I Will Follow, her intention was to set up the African-American Film Festival Releasing Movement (AFFRM), a new way to get films like hers in front of the audiences they're made for. With her second, Middle of Nowhere, she wanted to get into Sundance. But with Selma, her sole intention was to serve the story and that opened up the world. (I believe that when she set up an alternative distribution system that benefits others as well as herself she was already right into the 'service' principle and am awaiting the filmmaker who will co-ordinate the resources of women's film festivals along the AFFRM model!) And integral to this 'service' model seems to be the 'fairness' principle.

The Fairness Principle

I loved it in the Madame Noire interview below that when asked for one word that described what she'd like Martin Luther King's response to Selma to be, Ava DuVernay said–

I love the simplicity, the 'rightness' of the fairness principle because it extends the Activist CFP concern for gender equity within organisations to fairness in screen storytelling itself. It supports Geena Davis' suggestions for crowd scenes. It's a way to consider promiscuous protagonism. It works with normalization. It also makes it mandatory, I think, for the Activist CFP to consider every time 'Am I being fair?' Part of that, for those of us who are not women of colour, is to remember Ava DuVernay's 'There's something very important about films about black women and girls being made by black women…It's a different perspective. It is a reflection as opposed to an interpretation' and be very careful not just about who we place in the frame but how we do that.

We need to ask whether it's fair for us to tell stories with protagonists whose stories belong to a group we're not part of and therefore may be unfair to, in the same way that Hollywood has been unfair to women. For example, when I’ve assessed short films for American film festivals it's usually obvious when the makers have decided to make a film about ‘others’ from groups they aren't part of; this seems particularly common with doco makers. These films are often beautifully made from a technical point of view but don't feel 'fair'. In contrast, there are films made from within the community they portrayed. Sometimes these are a bit rough technically, but even when they are, they tend to feel 'fair' and to have a heart that transcends uneven skills. But there are lots of gray areas, as when I limp through the post, especially this part of this post, where I feel very uncertain! I believe that the Activist CFP needs to engage more deeply with a more energetic, open and ongoing debate about fairness in relation to whose stories get told, who tells them and how they are told. Are we reflecting? Or are we interpreting? It matters.

Fairness spreads to the work in other ways, too, many of them familiar to the women writers and directors I know. It's amplifies the kinds of acknowledgement that I've already detailed, in particular the careful attention paid to each person's contribution. According to Lily Loofborouw, the making of the new television shows is ‘different’ because the ‘glorified misanthropy’ of past practices has given way–

Fairness-of-access may also be why Gina Prince-Bythewood experimented with this Twitter party, the first I've heard of from a woman filmmaker.

From here, 'Hollywood' seems to be about big budgets, marketing and distribution. I know that there are many many women's films I'd love to see that have small budgets and don't get adequate distribution and have minimal marketing budgets. Many do not reach New Zealand, either because we're unaware of them and therefore don't watch them online if they are even available online, or because they don't have a Hollywood distributor (as Selma does) and/or because no-one will undertake the cost of getting them rated for what's perceived to be a small audience. So for me part of the 'fairness' lesson is to focus on imaginative ways to serve audiences of women and girls through distribution of our own stories.

Finally, I've inferred from these women's practices that significant artistic achievement does not preclude being an Activist CFP among the rest of us. It seems obvious, but continued engagement –on principle – with the broad communities of those working for change enriches the world where we are and nourishes us as well as others, through service to others and to our stories, through fairness.

Continuing As An Active Activist CFP

Remember the heartwarming Gina Prince-Bythewood tweet about the Love & Basketball script? Here's another one–

Ava DuVernay does it too, whether it's interviewing Gina Prince-Bythewood about her craft on the AFFRM programme The Call In, or, as she stated on that NPR 'Extra', by purposefully writing a scene in Selma that meets the requirements of the Bechdel Test and resisting suggestions that she remove it. Or appearing with Meryl Streep and Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy at the forthcoming Women in the World event, Story Power. Yes, it's possible to argue that these engagements are 'PR', 'audience-building' etc. But in view of the other principles I've identified, I think they are more than that. They're 'big sister' actions within a powerful ethical and sustainable framework that we can learn from. And be grateful for, as we do whatever we can to keep moving forward.

When I finish this little series of posts – and I'm still adding bits to this one, in late April – I will move forward myself. Begin again. Enriched by what these women have taught me.

But is that truly necessary? Is there an effective way for the Activist CFP to integrate her creative work with her activism? I’ve decided that it is possible. Jane Campion, for instance, continues as a rare high profile screen storyteller and Activist CFP. And women of colour are doing it too, especially African-American women who live in the United States, in closer physical proximity to Hollywood than the rest of us.

Over the last five years or so, women filmmakers of colour have arguably achieved critical mass, doing whatever they had to do to keep moving forward and distribute their work widely. They've always been around, of course, but because of the web-based information available it's become easier for the rest of us to access their work – though it's still sometimes problematic in New Zealand, for various reasons, including the rating system's cost. Since Ava DuVernay’s first film, I Will Follow (2010), there’ve been so many outstanding releases that have had wide distribution, like Dee Rees’ Pariah; Haifaa Al Mansour’s Wadjda; Amma Asante’s Belle (her activism is also inspiring and I'll refer to it in the next part of this series); Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night; Afia Nathaniel’s Dukhtar, Gina Prince Bythewood’s Beyond the Lights. (My favorite project-in-the-making from 2014 is Jacqueline Kalimunda's Single Rwandan Seeks Serious Relationship, being made between Rwanda, Paris and the United States and I love the generous vitality of Glasgow's Digital Desperados – thanks for the headsup, Kyna Morgan).

These films are not formulaic Save-The-Cat or Disney stories. They’re heartfelt and rigorous cinematic inquiries. Selma’s about leadership and radical change and community. Beyond the Lights and Belle explore ideas about power and how women of colour are framed. Wadjda and Dukhtar investigate ideas about being a mother and being a daughter. A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night plays with genre. Because of our new, larger capacity to access the work, because of the story choices and because of the strengths of the storytelling, it feels like there’s a shift from 'If we don’t tell our own stories no-one else will' (which always reminds me of Mira Nair's Maisha Lab, a non-profit facility for young directors in East Africa) to a new truth: 'We'll tell the stories we choose and tell them better than anyone else, and we will get them to audiences, who are hungry for them'. This has to have a run-on effect.

And the works I've mentioned are not one-offs. For instance, Dee Rees' telemovie, Bessie (Smith) is out on HBO next month. Ava DuVernay has multiple projects on the go, on various platforms, including a television series she's co-creating with Oprah Winfrey, based on Natalie Baszile's novel Queen Sugar. Ana Lily Amirpour is on to The Bad Batch, a dystopian love story set in a Texas wasteland, produced by Megan Ellison’s Annapurna Pictures and Vice. I love it that Haifaa Al Mansour’s next will be A Storm in the Stars, about the love affair between poet Percy Shelley and 18 year old Mary Wollstonecroft ‘which resulted in Mary Shelley writing Frankenstein’ (!).

(It interests me that in the United States, African-American women’s work seems to be represented more strongly than work by Latinas and Asian-Americans. I’m intrigued that in France, the most prolific film-making country in Europe, where many people of colour live, there appear to be few films by women of colour. I wish I knew more about women of colour working in languages other than English. I long for new features from Maori and Pasifika women. I wish for more films by and about queer women in their diverse communities, told by queer women of colour, like CampbellX’s Stud Life, as well as Pariah and Pratibha Parmar's doco Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth.)

So how do (some) African-American women manage so well to integrate their storytelling with their work as Activist CFPs? And what have I learned from them? Ava DuVernay's speech at SXSW (below) set me off on this section. I watched her talk about paying attention to our intentions, say 'Open up and make your intention be beyond yourself. Because if your dream is only about you, it's too small'. I listened to her speak about going into Selma with the intention of serving the story, heard her add 'I invite you to go inward and see what happens with an intention of service'. And I thought Yes! Activist CFPs are service-oriented; I think that every one of us has a dream for stories by and about women and that dream isn't just about us as individuals. And then I thought BUT. BUT an awful lot of Activist CFPs who are writers and directors aren't getting their screen stories out there to audiences. Certainly we're not doing it as often as Ava DuVernay and her African-American peers. What can I learn from them about combining CFP Activism with getting the artistic work done?

My perspective's limited by what I've been able to learn, of course. By who I am, a privileged white woman living in New Zealand. I'm an 'outsider' engaged in an investigation into how to combine screen storytelling with activism to create and sustain conditions where work by women artists flourishes and reaches wide audiences. From this multi-dimensional distance I may be utterly mistaken in everything I write about African-American women storytellers whose work I'm most familiar with. But I think that these African-American women exemplify the essence of the storyteller Activist CFP at her most realised and most generous, the richest timbre of the lioness' healthy roar as she tells her story.

Although Ava DuVernay's introduced me to these ideas, because she's so precisely articulated her philosophy alongside putting it into practice, I think there's evidence to support my contention that she's part of a long tradition whose time has come, rather than exceptional. And perhaps the time has come because there are new ways of doing things. By why have African-American women grabbed the moment(s) so effectively? In 2015, I suggest, African-American women's integrated philosophy and visionary work comes from their shared history and experience within a group that has been at least doubly colonised, under-represented and misrepresented on screen – as African-Americans and as women – and from the grief and the love that comes from this and the lived daily exposure to the terrible realities of broken black bodies. And from the inspiration of other visionaries like Dr Martin Luther King. (And I think that the very beautiful programme at New Zealand's recent Maoriland Film Festival may have arisen from similar histories and philosophies, or kaupapa.)

This is not to say that African-American women who are screen storytellers all think and act alike. For instance, I understand that Shonda Rhimes prefers to name herself as a screenwriter, director, and producer, not as an 'African-American woman screenwriter, director and producer'. Ava DuVernay calls herself 'a black woman filmmaker'.

And I imagine that when she calls herself a writer, director and producer without other descriptors, a person who creates content about anyone and anything, Shonda Rhimes is, like many other women artists, refusing any limitations. And from within that self-determination she's created new language to describe what she's doing,‘normalizing’ television–

I really hate the word 'diversity'. It suggests something…other. As if it is something…special. Or rare.In contrast Ava DuVernay chooses to portray the world through the lens of a black woman –

Diversity!

As if there is something unusual about telling stories involving women and people of color and LGBTQ characters on TV.

I have a different word: NORMALIZING.

I’m normalizing TV.

I am making TV look like the world looks. Women, people of color, LGBTQ people equal WAY more than 50% of the population. Which means it ain’t out of the ordinary. I am making the world of television look NORMAL.

I am NORMALIZING television.

There's something very important about films about black women and girls being made by black women…It's a different perspective. It is a reflection as opposed to an interpretation, and I think we get a lot of interpretations about the lives of women that are not coming from women.This reasoning seems very similar to that of many women artists who describe themselves as 'women' artists: it's self-determination again, a consciously chosen perspective.

And the two positions are common among women artists in various mediums I think. I remember a version of their presence when David Kavanagh from the Irish Film Board reported to last year’s World Conference of Screenwriters. When a group of women met to discuss his gender and film research and the dismal level of Irish Film Board funding for women’s scripts, there was an ‘angry’ debate. Some women insisted they write ‘differently’ and their scripts are therefore unattractive to producers and funders. Others counter-insisted that they write in the same way that men do. If you're reading this, you're likely to be someone who's decided to choose 'artist (of whatever kind)' or 'woman artist': myself, I'm sometimes one and sometimes the other, or both at once.

So in spite of their differences – and I bet there are many – what seem to be the principles that these women do have in common? I've identified a few that I think are essential to any Activist CFP discussion, especially for those of us who are screen storytellers. I imagine that I've missed a lot, but these are the ones that most affect me and inform my understanding of an ethical and sustainable framework for 'best practice' as Activist CFPs who are also screen storytellers. It's never easy and never will be, but I think these principles are very useful. The first group of principles is about identity: delight in who they (we) are, acknowledgement of where they (we) come from and of the achievement of others in the past and in the present. The second group of principles is about work choices.

Identity Delight

Regardless of artistic descriptor, this seems to be shared. Here’s Shonda Rhimes when she was presented with the Sherry Lansing Award (transcript here)–

I was born with an awesome vagina and really gorgeous brown skin.And Ava DuVernay, in the Madame Noire clip below–

I identify as a black woman filmmaker. That is who I am. I wear it proudly. I don’t think it limits me…It’s part of my adornment.It seems to me that delight in who they are generates a second principle– they consistently acknowledge where they come from. Sometimes this involves reference to those other visionaries, like Martin Luther King. Sometimes not. Sisterhood and brotherhood rule, with the named and widely known and the unnamed, the little known and the unknown.

Consistent Acknowledgement of Others

Here’s Ava DuVernay after she won Best Director at Sundance, years before Selma was nominated for Best Picture and Selma's 'Glory' won Best Original Song at the Oscars (where she said of the ceremony ‘this is just a room with very nice people applauding. But this cannot be the basis of what we do. This does not determine the worth of my work.’)–

[Winning] felt really good, but sad in a lot of ways. Bittersweet comes in because I know I'm not the first best black woman to make a film there– [there’ve] been a number of sisters that have made beautiful work there. Julie Dash, Daughters of the Dust, Gina Prince-Bythewood. I mean, many women have gone through. But for whatever reason, [the award] wasn't given. So I don't wear that with any kind of special pride–it was the time that it was given and I was there and I am grateful for it, because it helped the film and I think it's helped me. But I don't wear it as a definitive declaration that I was the first best director who happened to be an African American woman because I know it's not true. You got to tip your hat to the sisters who came before.Here's Oprah Winfrey articulating her version of the hat-tip, with a quotation from Maya Angelou's Our Grandmothers.

Shonda Rhimes,when she won the Sherry Lansing Award said this about 'breaking through the glass ceiling'–

… how come I don’t remember the moment? When me with my woman-ness and my brown skin went running full speed, gravity be damned, into that thick layer of glass and smashed right through it? How come I don’t remember that happening? Here’s why: It’s 2014.She urged the audience to look around the room at Hollywood women of all colours who have ‘the game-changing ability to say yes or no to something’. She talked about the differences for women 15 years ago, 30 years ago and 50 years ago. Then–

From then to now…we’ve all made such an incredible leap. Think of all of them… Heads up, eyes on the target. Running. Full speed. Gravity be damned. Towards that thick layer of glass that is the ceiling. Running, full speed and crashing. Crashing into that ceiling and falling back. Crashing into it and falling back. Into it and falling back. Woman after woman. Each one running and each one crashing. And everyone falling.

How many women had to hit that glass before the first crack appeared? How many cuts did they get, how many bruises? How hard did they have to hit the ceiling? How many women had to hit that glass to ripple it, to send out a thousand hairline fractures? How many women had to hit that glass before the pressure of their effort caused it to evolve from a thick pane of glass into just a thin sheet of splintered ice? So that when it was my turn to run, it didn’t even look like a ceiling anymore. …I picked my spot in the glass and called it my target. And I ran. And when I hit finally that ceiling, it just exploded into dust.

Like that.

My sisters who went before me had already handled it.

No cuts. No bruises. No bleeding.

Making it through the glass ceiling to the other side was simply a matter of running on a path created by every other woman’s footprints.

I just hit at exactly the right time in exactly the right spot.(And yes, Shonda Rhimes ‘makes stuff up for a living’ and the glass ceiling hasn’t gone. Shards remain, that’s for sure. And sometimes they wound women deeply. But she, Gina Prince-Bythewood, Oprah Winfrey, Ava DuVernay, have made it past that ceiling. Let's acknowledge and learn from that.)

And of course, if you consistently acknowledge where you come from, you also acknowledge those others whose work is just as significant as yours, right now. Towards the end of her acceptance speech, Shonda Rhimes thanked the women past (‘all the women who never made it to this room’), present and future, who are ‘all an inspiration’.

And here's Ava DuVernay again–

I'm not the only black woman like me; there are many women that I admire—black and brown women, women of all kinds, people in the quote-unquote margins, who are doing amazing things and telling beautiful stories. I may be the only one recognized by a certain gaze at this moment, but I'm not the only one doing the work.This awareness, this positioning among historical and contemporary communities, affects work choices.

Principles That Affect Work Choices

The first of these is that Hollywood and institutions like government funders (for those of us outside the United States, or who seek state tax credits within the United States) are not that important.

In one interview, Ava DuVernay said this, and I think it may be hard for many of us to hear it, because we have prioritised institutional change–

You know, I've tried to be really active in the institutional part of answering the question of how do you get women working. How do you get more women behind the camera? I do that by being on the board of Film Independent, being on the board of Sundance, trying to be as involved in that as I can with committees in the Academy.

Ultimately, women have to make movies, and we don't need institutions to do that. I think the more we can empower ourselves to know that there are other ways. We don't have to be authenticated by these structures, we don't have to be told that it's valid. We find ways to make it happen.

The first thing you make might not be the thing that your heart desires, but you just have to begin.Which is of course exactly what The Candle Wasters here in New Zealand have done and all the women who crowdfund are doing.

But it's hard for me to give less attention to institutional change and I suspect it's also hard for many other screen storytellers like me who are Activist CFPs and come from a white woman's place of privilege and entitlement. It's tempting for me to engage with white men's institutions and ways of working, white men's principles, the white male canon and the long long tradition of the solitary artist who's art-making dream is only about himself and involves no service to others at all. The other day, for instance, I read this, from Janet Frame, one of New Zealand's most distinguished writers (Jane Campion adapted her An Angel at My Table)–

I can read some of my books and see that I was toadying to the viewpoint of men. I'd just down and write and it would be something he said – and I'm freed from that now. But it took some time.If Janet Frame can admit to this and commit to moving beyond it, the rest of us have to think about it too. And perhaps make some changes. Work harder to de-colonise ourselves.

I think that one reason why many Activist CFPs like me tend to have Hollywood and state funders as primary reference points is because we believe that if we 'get it right' those white men and the women who work most closely with them will change. Organisations with power will change (and a few have). Or we'll be an exception (and some of us are exceptions and some of us work to hang on to being an exception, as evidenced when women directors voted down a Directors Guild of America motion that would advance women, just today). If we're 'good', those men will let us slip in to join them. Are women of colour, with good reason, less deluded than I've been and and therefore more likely to work 'differently'? I think that's possible.

Take Gina Prince-Bythewood as another example of someone for whom 'Hollywood' is not that important. She is the first woman writer/director I’ve heard assert that she turns down offers of work (from Hollywood studios!), on principle–

I’m offered movies all the time to direct. What’s discriminated against are my choices: I like to direct what I’ve written, and what I like to focus on are people of color. So that is absolutely the tougher sell, because there are no people of color running studios.Yes, she’s discussing discrimination here, but she’s also saying that – like Ava DuVernay – she will not work unless she writes what she directs and unless the work focuses on people of color. That's more important than any job at a Hollywood studio. The Activist CFP who is also a screen storyteller doesn’t always have such clear parameters. I sense that – unlike Gina Prince-Bythewood – we often so want (paid) work and to be an exception that we may compromise our personal standards.

Like Gina Prince-Bythewood, Ava DuVernay isn’t going to compromise her vision on the independent route she's adopted. The focus is on doing it, without asking for permission. No complaints about access to funds and other resources. Getting on with it, solving problems as they arise.

"Women making films is a radical act...Radicals don't ask for permission." #avaduvernay at #womeninfilm #sundance brunch

— Chicken & Egg Pics (@chickeneggpics) January 26, 2015

This is one version of her explanation for this position (which she expands on in many places, particularly in her her now-a-classic keynote address to Film Independent back in 2013 and which emphasises the minor role of Hollywood in her artistic practice) –I have not had a studio offer me a movie, flat out…Nope, not happening…It just doesn’t happen for us that way…It doesn’t really bother me because I’ve never operated from a place of anyone offering me anything…I just make my own stuff. I’m self-generating, and that’s just the way I started. I don’t boohoo about it; it’s just the way it is. And that’s the way I work.The second best practice principle that strikes me in relation to making the work is that it is necessary to serve others and to serve the story and that fairness is the most significant element within that.

Service of Others and The Story

In her SXSW address, Ava DuVernay says that she came by the 'service' principle (and its associated 'Open up and make your intention be beyond yourself. Because if your dream is only about you, it's too small') 'by accident, but now I'm going to try to do it on purpose'. She discusses how with her first feature, I Will Follow, her intention was to set up the African-American Film Festival Releasing Movement (AFFRM), a new way to get films like hers in front of the audiences they're made for. With her second, Middle of Nowhere, she wanted to get into Sundance. But with Selma, her sole intention was to serve the story and that opened up the world. (I believe that when she set up an alternative distribution system that benefits others as well as herself she was already right into the 'service' principle and am awaiting the filmmaker who will co-ordinate the resources of women's film festivals along the AFFRM model!) And integral to this 'service' model seems to be the 'fairness' principle.

The Fairness Principle

I loved it in the Madame Noire interview below that when asked for one word that described what she'd like Martin Luther King's response to Selma to be, Ava DuVernay said–

Fair...If you stay fair with it hopefully you'll get a story that is really complex and nuanced. And that's what we tried to do.And in the 'extra' to an NPR interview (as with the actors round table, it was worth tracking down what was edited out of the main story), she describes how that fairness extended to putting women back in their rightful place in the story, and to refusing to create composite characters because the women who held an array of roles in the movement were so full of life there was no reason to make anything up.

I love the simplicity, the 'rightness' of the fairness principle because it extends the Activist CFP concern for gender equity within organisations to fairness in screen storytelling itself. It supports Geena Davis' suggestions for crowd scenes. It's a way to consider promiscuous protagonism. It works with normalization. It also makes it mandatory, I think, for the Activist CFP to consider every time 'Am I being fair?' Part of that, for those of us who are not women of colour, is to remember Ava DuVernay's 'There's something very important about films about black women and girls being made by black women…It's a different perspective. It is a reflection as opposed to an interpretation' and be very careful not just about who we place in the frame but how we do that.

We need to ask whether it's fair for us to tell stories with protagonists whose stories belong to a group we're not part of and therefore may be unfair to, in the same way that Hollywood has been unfair to women. For example, when I’ve assessed short films for American film festivals it's usually obvious when the makers have decided to make a film about ‘others’ from groups they aren't part of; this seems particularly common with doco makers. These films are often beautifully made from a technical point of view but don't feel 'fair'. In contrast, there are films made from within the community they portrayed. Sometimes these are a bit rough technically, but even when they are, they tend to feel 'fair' and to have a heart that transcends uneven skills. But there are lots of gray areas, as when I limp through the post, especially this part of this post, where I feel very uncertain! I believe that the Activist CFP needs to engage more deeply with a more energetic, open and ongoing debate about fairness in relation to whose stories get told, who tells them and how they are told. Are we reflecting? Or are we interpreting? It matters.

Fairness spreads to the work in other ways, too, many of them familiar to the women writers and directors I know. It's amplifies the kinds of acknowledgement that I've already detailed, in particular the careful attention paid to each person's contribution. According to Lily Loofborouw, the making of the new television shows is ‘different’ because the ‘glorified misanthropy’ of past practices has given way–

… to a collaborative, egalitarian ethic that prioritizes community and caretaking. Liz Meriwether once said that the best job preparation for her work on New Girl was waitressing ('I was constantly dealing with hungry, angry people'). Jill Soloway is known for making even the extras feel welcome. Viola Davis, the star of How to Get Away With Murder told The Times how Shonda Rhimes… instructed her to prioritize her own well-being: 'Viola, listen, you’ve got to be taken care of. This show rests on your shoulders. Write a list of what you need'.

These approaches produce an ecosystem, both in the writers’ room and on screen, that allows and even expects to make an artistic contribution.And here's Ava DuVernay on the 'beautiful collaboration' of Selma, talking with Tavis Smiley–

...I think that kind of energy, that kind of emotional connection imbeds itself in the image in some way. That’s why it’s so important for me when I’m directing to create an atmosphere of just comfort and love and respect.

You know, I used to be crew. I used to be a publicist. I used to stand on these sets and be ignored. People walked past and, when they have to talk to you, they’re grouchy 'cause they don’t want to stop and people griping at each other. I just always said I don’t want anyone to feel that way on my sets.

So we worked very hard to create an atmosphere where everyone–the way that David is treated is the same way that the grip is treated. You know what I mean? The gaffer’s treated is the same way that Oprah Winfrey is treated. Well, maybe Oprah Winfrey gets a little…

Interviewer: A little more love, yeah [laugh].

Just a little. But, you know, like I said, I think it imbeds itself in the image and I think you can watch a film–I know that I can watch a film and tell when they were having a good time, tell when there was a good spirit on it.'Fairness'-within-serving-others can power marketing and distribution choices, too. Arguably, AFFRM grew from wanting to ensure that people who didn't see enough of their stories on screen had new opportunities to do so, had fair access. When I watched Selma I noticed that it would work very well on a tiny screen, another way to access it and imagine that was a conscious choice. And I loved it that 370,000 students saw Selma for free because African-American business leaders raised the money to make that possible.

Fairness-of-access may also be why Gina Prince-Bythewood experimented with this Twitter party, the first I've heard of from a woman filmmaker.

Finally, I've inferred from these women's practices that significant artistic achievement does not preclude being an Activist CFP among the rest of us. It seems obvious, but continued engagement –on principle – with the broad communities of those working for change enriches the world where we are and nourishes us as well as others, through service to others and to our stories, through fairness.

Continuing As An Active Activist CFP

Remember the heartwarming Gina Prince-Bythewood tweet about the Love & Basketball script? Here's another one–

.@BitchFlicks folks commend me on my female crews. truth is i surround myself with the best. they just happen to be female. #bitchflicks

— Gina PrinceBythewood (@GPBmadeit) March 17, 2015